Some advice for producers and others commencing the process of assessing livestock post bushfire. Its essential to seek help and to stay safe in this difficult task

What makes a profitable cow?

Are mature cows becoming too big?

Are our mature cows becoming too big? The nutritional demands of larger cows are certainly significant and have implications for ration amount and management decisions.

Tips for confinement feeding cattle in drought

Confinement feeding cattle has become a more frequently used strategy by producers as the drought continues to impact eastern Australia. Confinement feeding offers a number of advantages for producers who have made the decision to continue to feed livestock.

However to be successful some preparation ahead of starting the process is essential. And once the process has started it needs to be managed and adjusted to meet the changing needs of the cattle being fed.

One of the first questions I’m often asked is “why would you do confinement feeding?” It’s a good question, and there are several strong reasons for starting the process.

“Why would you consider confinement feeding?”

From a livestock perspective, the process allows you to bring animals to a central location and fed them to their needs. This can save a lot of time and ensure rations are more suited to the stock on hand.

Another key efficiency is the reduction on energy demands for livestock. Some interesting research from NSW DPI suggests that cattle in confinement feeding programs have around 8% lower energy demands as they don’t have to expend energy search for feed and water.

Courtesy of Ben Nevis Angus - Walcha

It offers some people the opportunity to feed rations that will allow cattle to gain weight or even grow to lay down fat and so meet a market specification. With the current price for cattle, particularly those with average fatness, this is a very attractive option for many.

For other producers, confinement feeding is a strategy to adopt as water resources become more limited. Rather than a series of temporary tanks and troughs across paddocks, it can be more efficient to provide water to a central point.

And from a pastures and soil management perspective, sacrificing a smaller area to preserve ground cover over the larger part of the farm and so allow quicker pasture response when the drought does break is a well proven drought management strategy.

So in order to successfully undertake confinement feeding of cattle, what are some of the key things to consider?

The first thing is to recognize that a confinement-feeding program is a temporary process for use in drought management, or from recovery from fires and floods. This makes it very different to a feedlot. There is a clear guideline on confinement feeding in NSW from the NSW Department of Planning and Environment.

The Department states, “Stock containment areas are used for temporary stock management arrangements and are not intended to be used as routine farming operations. They are distinct from feedlots, restriction facilities and other permanent works or structures.”

If you are thinking you want to construct a more permanent feeding facility, this does require consent and planning approval, so before you start you should contact your council and LLS for advice.

The location where you will undertake the feeding program needs some thought. It should be a site that is relatively easily accessible to provide feed, and to move cattle out. As a general guide I would suggest”

· The site should have some slope. Around 3 – 4% slope is considered ideal

· If possible use the top of a slope

· Avoid drainage lines or areas that are likely to become boggy hollows. As soil will compact any run off rain will quickly become mud and its best not to have that in the main area of the yards

While you cant always choose your soil type, its best if you can look fro the clay loam soils. Heavy clays will become an issue in wet weather.

The other key issue around location is distance from your house and neighbours! There will be odour, dust, flies and noise, so you should consider trying to be at least 500m from anyone’s home.

Deciding on the size of the yards or paddock may not always be straightforward. It will depend on location and on the number of stock on hand. Its important to remember that high density will create problems on rainy days with bogging, while excessive numbers can cause dust that impacts stock and people.

The NSW DPI recommends that cattle should be kept at the following densities:

· Weaners: 9 to 10m2 per head

· Yearlings: 12 to 14m2 per head

· Dry cows: 15 – 25m2 per head

It’s important that no more than 250 head are kept in any one mob. And for early weaned calves it should be no more than 100 head.

“I always recommend drafting cattle into groups based on fat score, weight and frame size”

I always recommend drafting cattle into groups based on size and weight. Ideally I would have cattle drafted on fat score and weight and have a spare pen or yard on hand to draft sick animals or shy feeders off and manage those separately.

Well designed yards allow rations to be easily fed

Confinement yards can be constructed out of normal fencing wire. Most people convert small paddocks and so the standard 5 strand wire is adequate. Some people do add an electric wire to ease pressure on fencing, particularly if they use fences as part of their feeding system.

Feeding in troughs is a preferred method to reduce waste and avoid intake of soil and disease. However I know quite a few people who have chosen o feed between two fences onto the ground. Over time the ground does pack down and wastage is much lower as a result. So it may be an option to discuss as you make your plans.

What is important is to ensure sufficient space to allow animal’s access to the rations. If a daily ration is offered into troughs the following spaces are recommended to ensure easy access:

· Weaner cattle 30cm / head

· Yearling Cattle 40cm / head

· Adult Cattle 60cm / head

Horned cattle may require additional space so this needs to be considered in your planning.

Troughs can be as simple as conveyor belt, and I have seen many made this way. I’ve also seen troughs made from folded tin and from hollowed tree trunks. As long as they are accessible to stock and can be cleaned to avoid mouldy rations I think they are ok.

Troughs can be made of conveyor belt at a low cost

However troughs should be 45–60cm wide and deep enough to hold the ration with the top of the trough maximum 60cm from the ground. A trough that is 10–15cm higher at the back (outside) reduces wastage. For young stock, troughs that are too deep can cause baulking due to poor vision, while those too high can affect feed access and intake.

Finally don’t forget water. Cattle will drink up to 100 litres in summer and in hot weather this can increase by up to 80%. Cattle prefer to drink water between 16 – 180C and as water gets hotter they will drink less and this impacts their feed intake and general wellbeing.

Ideally troughs should be deep enough to keep water cool and if water is piped from a tank it should be underground to avoid excessive heat.

When a trough is sited, try and place it as far from feeders as possible. At a minimum this should be 10m. This helps reduce contamination from feed that may still be in an animal’s mouth. Another suggestion is toplace troughs along fence lines can so stock on both sides of the fence can use it.

Troughs should allow 10% of a mob access

Water troughs need to be long enough to allow at least 10% of cattle in the mob to drink at any one time allowing a minimum of 300mm space for every 10 head. For example a 3m trough can water 100 head. It’s worth working out trough size before you settle on final numbers in a pen if you only have a limited amount of water access.

There are plenty of tips and experiences people have had in using confinement feeding as a strategy. If it is something you are planning to undertake, it’s worth getting in touch and seeking some advice. Some of the tips and ideas people have can be big time savers!

Early Weaning - Not Just Set and Forget!

Early weaning is definitely one of the more frequent topics for discussion among producers. As the drought continues to impact on businesses, many producers are looking at other management strategies within their drought program.

Early weaning is certainly a very important strategy, and can be used to successfully care for cows and ensure calf growth can be maintained. However, as a strategy it does require some planning and has to be done with a daily focus on ensuring calves are responding to the program. There are no shortcuts if you do choose this strategy!

Managing cow condition is a key reason for early weaning

As a strategy to manage cow condition, early weaning can be a vital tool in a drought plan. The minimum amount of feed a lactating cow requires each day is 2.5% of her body weight and that this feed should be a minimum of 10.5 ME / Kg and 13% CP.

This compares to a dry cow requiring only 1.8% of bodyweight a day and at an energy level of 8 ME / Kg and 8% CP. By early weaning you have a chance to adjust rations and focus on using high quality rations on those cows that are very light in condition and need special care.

If your cows are light and certainly anything that is AT RISK (Fat Score 1) then you should be planning to early wean the calves and look after the cows as a seperate group .

One of my first tips for early weaning is to plan ahead and ensure you have adequate facilities. This means having well secured yards that has access to clean water. Water intake is essential to ensure calves meet their daly intake requirements. Having an old bath tub that gets filled up once a day is NOT acceptable!

Your calves need to be drafted into groups that are of simile size. Generally this means they will be the same age. However size rather than age is the predominant consideration on drafting. I tend to recommend three groups. A small, medium and larger group. You also should have a spare pen. I call this the hospital group. Anything sick or not doing well should be put into this pen where you can give the calves some more specialised attention.

Draft your calves into similar size groups

Your rations need to be introduced slowly. It’s important to provide roughage that is of good quality. Poor quality roughage is often a limitation to intake. And you often find calves would sooner play with it rather than eat it! So its worth avoiding stubble hays.

Most people now use prepared pellets. Pellets are a convenient option and allow producers to feel confident in managing protein and energy levels. Protein levels (CP%) need to be between 16 - 18%. You should introduce pellets slowly. Build up to the amount that you are aiming for (based on the weight of the calves).

Feeding daily is more preferable to using self feeders. Firstly this allows you to monitor your calves and draft off any sick ones. Secondly it does prevent over eating and bloat occurring as some animals will hang around a self feeder and gorge themselves. Of greater concern can be shy feeders who hang back until the self feeder is free and then over eat. This often results in bloat.

“Feeding early weaned calves is a nursery job so you can not just feed them ad lib and get on with the other work”

Feeding calves in an early weaning program requires attention and a daily program. While I’ve seen good success with self feeders in pens, I’ve also seen some real problems!

Making sure each calf gets its daily ration is essential. Feeding in a trough, as long as the space is adequate (around 20 - 30cm head) gives your calves the opportunity to consume their requirements. It allows you to manage for issues like sickness or to remove dominant animals or those larger ones and place them into other pens.

If you do use self feeders then you need to make sure there will be enough space for the animals in each pen. So maybe you need more than one feeder per group.

If you do use self feeders, ensure you have enough room for all the animals in the pen

Early weaning can be a bit stressful on calves, and this can impact their immune system and general health. I definitely would be ensuring all calves were vaccinated with a minimum of 5 in 1 against the clostridial diseases.

This year several of the vets I work with have suggested calves coming from drought conditions would also benefit from a treatment of Vitamins A, D & E. So this could be something you also need to factor into your plans.

Ultimately early weaning can be a key part of your drought program if it is planned and managed as a key job. A daily feed, regular inspections and a planned ration are all vital for success. If you do want to plan a program and want some input, don’t forget you can get in touch with me and I’ll be happy to help you put a plan in place.

Producing Optimal Carcasses

What does it take to produce an optimal carcass?This is a question that producers often ask.While there are a number of things we can do as livestock managers, I think the first step it to actually define what an optimal carcass means.

In my mind, an optimal carcass is one that meets the target specifications for weight; fatness, eating quality – MSA Index and has a high yield of saleable meat. I also think this is something that producers need to do consistently, and do so with the most efficient use of resources. There are a few steps I think producers focused on optimal carcass production need to consider.

Clearly define the breeding objectives for your herd. I’ve often talked and written about the importance of defined breeding objectives. The reason being, these objectives define the type of genetics you need to use to meet your market and to breed cattle suited to your program.

Know what you are actually trying to achieve! Markets are well defined for weight, fatness, and eating quality. If you know what these specifications are, you can start to plan on the process of growing to meet these. Specifications are readily available from processors and from feedlots. So you need to get in touch or at least look at the specifications on company web sites and choose realistic options for your program.

Focus on what you can control. There are three key areas you control as a producer. These are:

Maturity pattern: This determines the ability of your animals to meet specifications. It also impacts on productions traits such as fertility, so you need to consider both aspects in order to be productive and profitable.

Growth rate: Your ability to choose the correct genetics, and to manage nutrition to express those genetics, has a massive impact on optimal production. Using EBVs and feedback from previous sales can help you fine tune growth rates. But you still need to manage pastures, crops and supplements to make that growth happen.

Finally, you need to manage the way you finish and sell animals: The final stage of production, selling and transport can derail your program. Stress, poor handling or other factors can impact on your eating quality index and cause you to miss the optimal. So this final stage should be managed as carefully as your genetic decisions or feeding programs.

Managing Growth

A large part of optimal carcass production is the management of growth of animals. This actually starts with your choice of genetics. The ability to select for growth using EBVs is an opportunity you shouldn’t overlook. It’s well proven by many research and commercial trials that, EBVs do work and can be a very effective tool for producers.

However, genetic potential can and is often limited by nutrition. Growth is a function of the daily intake of energy and protein. Ensuring your cattle have sufficient to maintain growth paths is the practical aspect of management.

The CRC for Beef Cattle highlighted the impact growth paths have on carcass yield, fatness and eating quality. The research showed quite markedly that slow pre weaning growth resulted in cattle that were smaller than normally grown cattle.

However these slower grown cattle never catch up in weight, even in feedlot conditions. The simple message being that to meet carcass weights, these cattle had to be grown longer, and this ran the risk of impacting carcass fat specifications or lowering MSA Index values. Either way, slow pre weaning growth is not ideal

Slow post weaning growth was also researched. It was found that slower than the optimal 0.7kg / day resulted in cattle that grow faster in finishing programs. They tended to be a bit leaner and have less marbling. So if this is an issue for your markets, this may also be a path to avoid.

The CRC data really suggests we aim for 0.7kd / day for animals up to feedlot entry. To do this, you should remember that your cattle will need to eat at least 3 – 3.5% of their live weight on a Dry Matter basis each day. Ideally this feed would have a minimum of:

Energy 10.5MJ / Kg

Crude Protein 14%

Fibre 30 – 40% NDF

A simple rule to remember is that the faster your cattle grow, the fatter (and slightly more muscular) they will be.

Eating Quality

There are many factors that have an impact on MSA Index values. As producers, its important to focus on the ones that have a high impact and are controllable on farm. High impact variables include Marbling and Ossification.

Your genetic selection and nutritional management will influence your animal’s ability to develop marbling. It’s a trait worth considering if this can be selected for without compromising your other production traits. Ossification, can be improved by growth rates and achieving higher weight for age. Again it’s important to balance this with other traits that matter to you, like carcass fatness and marbling.

The amount of Tropical Breed Content will impact on your MSA Index. But you need to be realistic. If your environment is nest suited to Indicus cattle, then you should use that to your advantage. You can still select for growth, marbling and fatness and achieve MSA Index scores that are quite high if you manage these traits well.

How you sell your animals also has a huge impact on your ability to meet optimum carcass specifications, particularly for eating quality. The work done by MSA highlights the impact that sale yard stress and handling has on eating quality. Cattle sold through saleyards have MSA Indexes that are 5 units lower than those sold direct to processors.

Summary

Producing optimal carcasses does require some serious attention across genetics, nutrition, and turn off. More importantly, if you don’t have a clear idea of what your optimal carcass requirements are, and utilize past feedback to fine-tune your program, you’ll find it a much harder challenge. Having some clear objectives and using the tools that are now available is the key starting point for anyone determined to consistently hit their targets.

It’s important to remember that if you are not entirely sure where to start, to seek advice or help to define your goals. Its one of the services I’ve been delivering over recent years, and it's certainly something you may want to consider in your program.

Whats your attitude towards farm safety

In Australia, Farm Safety week is generally held in the third week of July.The week is an opportunity to focus on the issues surrounding farm safety and ways to reduce the risk to farm staff, farm families and visitors to farms.

Personally I don’t think a week is long enough! Farm safety should be the priority for all us every day! The statistics around farming accidents are quite frightening. The National Centre for Farmer Health highlighted some of the statistics:

“In 2017, the rate of work-related injury fatalities for agriculture was 16.5 deaths per 100,000 workers. Agriculture continues to be the highest risk occupational group—with over 10 times the rate of fatality when compared to the general employed population. 27% of all work-related deaths occurred in the agriculture, forestry and fishing industries”

“Workers over the age of 55 years account for over half (55%) of all fatalities, with two-thirds of all deaths occurring in sheep, beef cattle and grain farming. Children under the age of 15 years are also a high-risk group, particularly when playing or helping out with farm jobs.”

The concerning issue is that in the past 10 years or so, the level of injury and deaths on farms haven’t really changed. So I reckon we really need to do more to reduce those risks.

So why is farming so dangerous? I think there are many reasons. The combination of issues associated with working with machinery and large, fast unpredictable livestock can be a risk. I also think that when you combine stress, fatigue, weather and exposure you increase the risks. Lastly I think there is a real risk called “attitude”.

For some reason there is an attitude towards farm safety that sees trying to be safe as being “soft”. This week I’ve been sharing posts on Facebook about Farm Safety. The response to these posts has been interesting.

For instance, did you know that horses and cattle are the most deadly animals in Australia? In the years between 2008 and 2017, horses or cattle killed 77 people. In addition the number of serous injuries was significant. I know several people who have suffered significant injuries working with cattle. In response to that post, I received comments such as:

“We don’t all push pencils you know. Leave the bush to the bush let us do what we got to do.”

“If it is the life style you like you will not be worried about the knocks and bruising. If you do not like the chance of being hurt find another job.”

I find this interesting. A little research shows many of these comments come from young males. There is a level of friction there that sees thinking about safety as being something that will stop them enjoying their job or their career.

But will it really? Being safe in your job is something we all have to consider. It is the law, and we have a duty to ourselves and others to look out and manage safety at work.

Doing your job and thinking safely doesn’t mean that everything has to change. Some things are always going to be inherently dangerous. But there are ways to make the job safer.

I use a risk matrix for many of my jobs now. I’ve been using this largely in response to my roles as a leader and manager of other people. When I was a fireman the most important consideration was that none of my crew would be injured or worse. And its no different with my clients or co-workers. I want to look out for them.

The matrix looks at what is the risk of an event occurring (its likelihood) and the consequences of the event happening. Now just because an event or a job is considered high risk, doesn’t mean it cant be done. What it mean is you have to think about ways to reduce the risk.

Can you reduce the risk by changing the way you do things? Can you reduce the risk by a mechanical means – e.g replacing a head bale on a crush; a guard around a silo ladder; or can you remove the risk. Would some training help? Simple changes could be the difference between an event being high risk or medium risk.

Not long ago I saw this statement

“One reason people resist change is because they focus on what they have to give up instead of what they have to gain”

I think this pretty well sums up lots of responses to farm safety. Making a change to be safe doesn’t mean losing your ability to enjoy being on a horse, driving a tractor or doing any of the other tasks we do in agriculture. But if you can take a few moments to assess the risk, think if there is a safer way and work to that, you will be that one step closer to coming home safe every day.

Prepare for the cold fronts!

The impact of cold weather on your livestock isn’t to be underestimated. So far this July we have already seen several strong cold fronts sweep across southern and eastern Australia. These fronts have been accompanied by strong winds, snow and sleet and then days of intense frosts.

These events have a big impact on your livestock. The demand to stay warm requires extra energy. At present the intense drought conditions mean many livestock are low in body condition and surviving on minimal rations. The combination of low body reserves and reduced energy intake means your stock is less able to cope with the cold, and at greater risk of dying.

How does cold affect your cattle?

We often assume cattle can cope with cold conditions more easily than other species like sheep. However, cattle can be just as impacted by the cold as any other species. As a warm-blooded animal, cattle have a normal temperature of 380C. Under most circumstances cattle can cope with some temperature fluctuations without needing to expend too much extra energy. As the season changes they grow thicker coats, and in periods of cold weather they change their grazing patterns to find shelter.

However this behaviour can only go so far. If temperatures fall to what is known as the ‘lower critical temperature” your cattle will start to be cold stressed. To cope they start to require more energy to stay warm. And in this situation they need to have more energy in their diets.

Some research by the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture in Canada identified the differing levels of lower critical temperature, depending on cattle coat thickness. These levels do vary depending on coat thickness.

These temperatures don’t take into account the impact of wind speed. Wind has the biggest impact on the lower critical temperature. This can be seen below

Looking at the table, if the wind was only 8km /hour on a 40c Day, the actual air temperature is really 10C.

This is close to the Lower Critical Level for cattle with a dry winter coat. But a wet coat after rain means your animals are at real risk of cold stress.

Cold and wet conditions have a massive impact on sheep programs. At greatest risk are lambs that are often unable to cope with the impact of cold weather. Rain and moisture significantly increases the risk of mortality. As with cattle, sheep manage to cope to some degree with cold by changing behaviour and seeking shelter. They also have a fleece that will offer some protection.

However its important not to overestimate how effective a fleece may be. The table below highlights the Lower Critical Temperatures of Sheep

As with cattle, when wind speed increases, the impact on Lower Critical Temperature is much greater. And for lambs with no fleece and a large surface area and low body mass, their energy loss is very high.

Managing the Risk

In practical terms it's impossible to avoid cold fronts. However we can manage for them. The options that are available to help your stock cope with cold conditions include:

Increasing rations ahead of the cold front: Hay is a very good option to increase a ration. It is more slowly digested and the process of digestion helps stock stay warmer as well as getting more energy. However it’s no good just offering a bit! You need to increase your rations by 10 – 20%. If your stock are light in condition or slick coated cattle I’d definitely be increasing to 20% ahead of and during the cold period.

Provide shelter. Breaking the wind speed up can have a dramatic effect on improving conditions for your stock. Moving them to sheltered paddocks that have trees and shrubs that break up the wind will be vital. There are plenty of well proven strategies and studies that show the role shelter has in livestock survival

Longer term, consider developing shelterbelts and wind breaks to moderate the wind across the farm. You certainly can’t grow shelter over night, so in the short term consider what other options you have to shelter your stock.

Cold fronts often only last for a few days, and with adequate warning you can prepare your stock to cope with the challenge. It is important to make your plans happen when the fronts are forecast. Don’t leave it to the day of the windy and snow to start doing something. Often moving stock in those conditions makes it worse not better! Pre preparation is everything to give your stock a chance!

Are you properly prepared to buy a new bull?

Purchasing new bulls for a program is a significant event for any producer.While many people consider the immediate cost of the bull to be the most pressing consideration, there is much more to consider than his actual cost! A bull will make a contribution to a herd that will extend for up to 15 years. So the lifetime cost of that bull in a herd is much greater than what you may pay at auction.

I spend a lot of time with producers looking at bulls before sales. I’m often conscious that a large number of people I chat to have only a general idea of the characteristics of the bull that they want. As I wrote earlier, the question “what do I think of this bull?” is a hard one to answer. As we approach the spring bull selling season I’ve prepared a few suggestions to help producers prepare ahead of their next bull purchase.

Know what you want to achieve in your herd

A new bull should be the source of genetics to help move your herd closer to your goals. So you need to be very clear on what you want to achieve. I’d normally start by considering:

Your current market – are your steers and heifers meeting the weight, fat and eating quality specifications?

Your environment – are your cows the size that suits your pasture growth patterns throughout the year

Is your herd fertility as high as it can be? Are your cows going into calf early, delivering calves easily and rearing those calves to weaning?

Are there traits you would like to improve further or correct with genetics?

These are four key questions you should be focusing on as part of your business planning anyway. In terms of seeking a new bull, the answers to these questions will give you a focus on the traits you should be seeking.It’s equally important not to rush this process! You really need to take some time and review the market feedback you have, your fertility data and your paddock notes to see why you have been culling certain females from the herd.

2. Search for bulls well before the sale

If you have identified the traits of bulls that you want bring into your herd, you should start doing some preliminary searching. There are various ways to do this.

Use breed websites to search for bulls with specific EBVs that meet you criteria. This can be useful, however it may mean you need to do some additional searching to find the bulls you have identified with a particular breeder.

I use on line sale catalogues available through the breed websites. This option will bring up the bulls listed at your chosen breeders sale. The easiest way to find the bulls that suit your criteria is to click on the option that asks if you would like to link to Breed Object. This will bring up the bulls with their EBVs and Index values, which makes searching much easier.

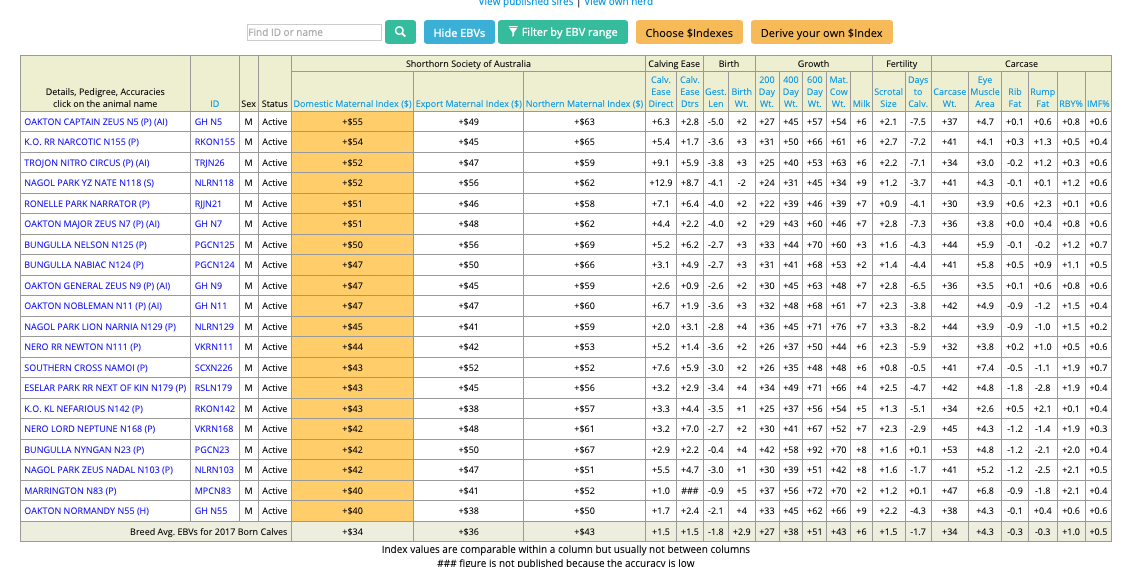

3. Use the Indexes

Indexes were developed to help make selection easier in a couple of ways. The first is to remember that Indexes are developed to reflect both the short-term profit that would come from using a bull through his actual progeny. While longer term profit is the influence his daughter have on a herd. The Indexes combine the animals EBVs for their impact on the traits that impact on a specific production and market system.

I personally tend to find the Index that best suits a program and look at the top 5 bulls in the catalogue. If you need to adjust a trait for a reason, one that you have identified earlier, you can then go and fine tune your selection on specific EBVs.

4. Talk to the Breeder

Breeders have an interest in helping their clients. However you also need to make sure that the breeder you are approaching has the same focus or direction you have. Ultimately you have to be confident you are buying bulls from an operation that has the same focus and scrutiny you have for your own herd. You need to do this well in advance of a sale. Trying to make that decision on sale day is never a good idea!

5. Have a physical checklist for sale day

I’ve been to hundreds of bull sales. I know that some people find them exciting and a great day out. Some people find them over whelming and get swamped by the event. You need to go to a sale with plenty of time and a mission. In short you need to:

Arrive early and spend as much time as you need looking at your chosen bulls. Don’t worry about the other bulls in the pen, or what other people like or don’t like! Your herd is your concern and the bulls you’ve identified are the ones that meet your objectives.

Look at those bulls and have a checklist. Are the bulls structurally sound? Do they reflect your maturity pattern? What is their temperament like? Do they have the muscle pattern you need?

Ultimately you need to use your research and stick to the chosen selection. These bulls are those that fit your needs. Don’t agonise about who is better in one trait but not another. If they are all bulls that are in your specifications, rank them in preference, but then treat them the same! Then in the pens use your observations to chose the best on the physical traits that you want. If you do that you’ll have a preference list. These and only these are the bulls you need to bid on!

If you do this properly you’ll have time to enjoy the steak sandwich and the social catch up! You’ll also find that when you ask me ‘what do I think of this bull?” I’ll be able to have a much more useful conversation with you!

What do I think of this bull?

One of the most frequent questions I’m asked is the simple “what do you think of this bull?” For such a simple question, there isn’t a simple answer I can give. Occasionally I am tempted to say “not much” but if I am stalling for time I might fall back on the standard “I haven’t really thought about him yet”. Either way, the question is one that is a challenge and requires a little time to consider a proper response.

My greatest challenge with this question is the context it’s being asked within. Selecting bulls is a key task for any breeding program. The decision made to use a bull is the start of a process that will effect up to three generations of cattle and play put over 15 years.

In that context, decisions around bulls need a lot more time than a quick “what do you think of him”.

Ultimately I try to get the person asking me that question to share more about what they are trying to achieve at home. In simple terms, what are they breeding for? What are the traits that matter to them. Are there issues in the cow herd they want to focus on. Is there an issue with suitability to their markets or the environment.

These are all the basics of a breeding objective. If you know that, you can start to determine if the bull is suited to their program or not.

The other challenge is when a producer comes up to ask what do I think of a few bulls, brandishing the raw data that is provided on the bulls. I have to be honest and respond that I need a lot more information before I give a comparison. Quite simply I don’t find raw data all that helpful, except to provide me with a weight of each animal on the day. Other than that, to me it doesn’t offer anything terribly helpful in determining how a bull will fit into a programs objectives.

It’s very easy to compare bulls for visual traits. In fact I think that’s essential. So I am very happy to assess the muscle patterns, structure and gait of a bull as he walks around the pen. I can look at his maturity pattern and make some comparisons with his sale mates.

And I can see what his individual temperament is like as I follow him around assessing his physical attributes. But, what I cant see and compare, is the genetic potential those bulls offer without accurate data.

Raw data that is often provided at bull sales shouldn’t be seen as an insight into the potential of the bull. With these supplementary sheets it's important to remember that these sheets record what the bull as an individual has done to that point in time.

So when you look at that data, or when I have it shown to me, its important to acknowledge the role that nutrition and the pedigrees have in determining a particular bulls phenotype, these are not the only two areas to consider.

There are many additional influences, ranging from the bulls age; the age of its dam; was the bull a single calf or a twin or if it was produced as a result of ET?

These are all non genetic influences on the bull that impact over and above nutrition and genetics. And when you are standing in a paddock looking at those bulls, it’s very difficult to know what these additional influences are or how to account for them in a selection decision.

My greatest concern is that often producers end up selecting on differences that are a result of these multiple factors, rather than for the genetic differences in animals. Selection on raw data is further complicated by the heritability of individual traits. Highly heritable traits such as coat color can be an easy selection decision, as these traits can be easily passed on to progeny.

However, as a trait becomes less heritable it is harder to see these differences reflected on the basis of raw data alone. Producers attempting to manipulate traits to meet breeding objectives in areas such as female fertility have a harder job to select for improvement when they are reliant on raw data and visual observation. Its not an impossible task, however it is a much more difficult, and drawn out process over several generations.

As if this isn’t difficult enough, there’s something else to remember! That’s the relationship between the trait that has been recorded and the traits that are the focus of particular breeding decisions?

Not all traits follow linear progressions. A good example is scanned data for EMA. The size of EMA at a particular point in time may not be reflective of increased muscularity, but rather a result of growth rate to that point in time. A larger EMA may be more reflective of the growth and weight of the animal when it was scanned.

It really concerns me when producers place all their emphasis on the raw data of animals as the basis for their selection decisions. Without knowing the cumulative impact of the environment, feed, and other non-genetic factors, bulls are being selected more on reflection of the year’s circumstances, rather than on their genetic capability. This often works in a counterproductive manner to selection pressure placed on the breeding group at home.

So if you are choosing bulls, you need to make this a project and allow yourself some time to make decisions based on research and preparation, rather than a comparison of animals on the day of the sale! There is tremendous value in spending time considering what you want as an objective for your herd, and looking at a range of bulls to help achieve that goal.

Breedplan figures and the search tools in Breedplan can help you find the bulls that could suit your program. Then you can go and look at them and see if they physically have structure, the muscularity and temperament to suit your program.

If you do that then when you ask me what do I think of these bulls, I’ll be able to have a focused and hopefully more helpful discussion with you!

Selection to Increase Saleable Meat Yield

As cattle producers, we are focused on the production of red meat that can be used to feed people. I’m not sure that many people really know just how much red meat comes from their cattle. I think it is an important trait to consider and work on improving. After all increasing red meat yield per animal is a more efficient way to use your feed resources and be more profitable in the long term.

When considering Red Meat Yield, its important not to be confused with Dressing Percentage. Dressing percentage is commonly talked about by people and confused with yield. In simplest terms, Dressing Percentage is simply the carcass weight of an animal as a percentage of its live-weight.

Dressing Percentage is a useful tool to measure and to understand, particularly for producers who are looking to market cattle direct to abattoirs. Knowing how your animal will dress and so fit a payment grid can make a big difference in receiving the grid price or suffering a discount for being over or under the weights.

It is important to remember that Dressing Percentage is influenced by factors associated with an animals live-weight. In particular the length of time off feed and water. A simple rule to remember is that as live-weight decreases, Dressing Percentage will increase. Other factors that can have an impact include pregnancy status (cows and heifers) as well as grain or grass finishing programs.

So Dressing Percentage is something that has to be considered and managed in order to achieve optimum returns when livestock are sold over a grid. However focusing on the yield of red meat should be a major focus for producers.

In basic terms yield is generally described as Saleable Meat Yield (SMY). It is defined as the proportion of the carcase that can be processed and sold to the consumer. This includes all the bone-in or boneless cuts that we commonly see at retail level, plus manufacturing meat that has been trimmed to a desired fat coverage or level.

The level of Saleable Meat Yield (SMY) can vary dramatically among animals. A real issue for processors or butchers is this variation will impact the efficiency of processing or retailing. It basically costs the same to process a carcase into its primal and retail cuts.

Lower yields either as a result of less muscle or over fatness, quickly become financial issues for that portion of the supply chain. In the longer term it reflects back on the producer who may find their lower yielding cattle are purchased for lower prices or avoided all together.

As producers the challenge is to increase the amount of saleable red meat each animal produces. There most effective methods are to focus on meeting specifications for fatness. Over fat animals require more trimming, and this impacts on the amount of product for sale after processing.

The second and major way is to focus on selection for muscle volume within the herd. This can be done using both EBV’s that address meat yield, and to visually select animals for their muscle score.

Over many years, NSW DPI has researched the impact muscle score has on saleable meat yield. One of the key findings from this research showed that selection for muscle score was a skill that could be used in all beef herds.

More importantly the research highlighted that for each increase in muscle score at the same live weight and fat depth, dressing percentage increased by 1.7%.

Saleable meat yield as a percentage, increased by 1.5 to 1.7 % and lean meat yield (denuded of fatness) increased by over 2%. In lightweight steers, this equated to 10–15% increase in value.

The research looked at this over three steers that were all the same live-weight and fatness. The additional increase in yield of saleable meat through increased muscling was a significant contributor to the value of those animals to both producers and retailers.

In the last few weeks I’ve been working through these concepts with several producers to improve their herd’s suitability to several emerging markets. We have also been looking at the breakdown of a beef carcase and the proportion of red meat from each primal cut. Selection for muscle has a positive impact on increase the amount produced as well as improving the shape and appearance of these muscles when they are processed into retail cuts.

Judging steers in a show ring

Preparing and showing steers is perhaps the most common of all livestock showing in Australia. I know for many people steer competitions are the starting point in their livestock career. In my own case, showing steers with my school was an integral part of my exposure to the broader industry.

Steer competitions allow many young people the opportunity to learn a range of responsibilities and gain skills and knowledge that can be used in their future careers and in their broader lives.

Preparing a steer requires knowledge of selection, nutrition and a commitment to ensure the steer grows according to a specific end point. For young people there is the responsibility of not only feeding and caring for the animal, its also about the preparation and training.

So what brings success in a steer ring? As a judge I have some pretty clear expectations for steers. The things I consider are important not just for the show ring. I am looking for the traits that are economically and commercially relevant. Through judging I hope that people preparing steers, learn to use that experience in their approach to commercial operations, and so produce more economically valuable animals for themselves and for the clients they hope to attract.

The traits that matter

Whenever I consider a class of steers, my first thoughts are about the class specifications. Specifications for weight and fatness are essential! The processor for various reasons sets a weight. These range from;

• ensuring that the primal cuts that the carcass will be broken down into are the correct size for further fabrication into retail cuts

• efficiency of processing within a plant

• ease of processing. For example a local butcher has smaller lighter bodies both for retail purposes and for the simple reason that there isn’t enough room in a small chiller for a larger carcass!

If a steer is too heavy or too light for class specifications, I automatically discount it as a place winner. In the commercial world this discounting happens with a lower price offer from the purchaser.

There are some important lessons to consider beyond the obvious discounting for price (or points in a competition). If your steers are too heavy then they should have been entered into a different class. Or in commercial operations sold to a heavier market.

If you don’t direct cattle into the appropriate market then not only do you receive a lower payment, you have also lost money and time growing extra weight that isn’t being financially recognised at sale. So effectively you are costing yourself more money.

My second consideration for class specifications is for the specifications for fatness. Again there are fat depths set for a reason. These include the minimum required for MSA grading (3mm on the rib) as well as to ensure an evenly covered carcass. Over fat cattle create more issues with excessive trim.

Again the consideration is not just the discounting that occurs for over fatness, but the cost and time spent to lay down this fatness that is then wasted.

The lesson to consider is that if you are preparing steers, for competition or for the market, know your specifications! If you are failing to meet the specs, does this mean you need to consider:

• Feeding program – are you growing at the optimum daily rate for your target? If it is too slow will you fall below the minimum? Too fast and will you overshoot?

• Fatness – Consider not just your feeding but also your animals maturity patter. Is your maturity pattern correct for your target market / class specifications? Later maturity animals lay fat down later, so will you be able to meet the requirements with your maturity pattern. Similarly are you not being too ambitious with early maturity patterns?

Once I’ve considered the suitability of the steers to their class specifications, I assess each steer for its overall muscle volume. Muscle is directly related to saleable red meat, and so the more an animal has, the more saleable red meat is available and so the value of that animal increases.

I assess muscle volume using the industry accepted muscle scores. I find it useful to think about volume in the same way it is calculated for any shape. Essentially it means to consider length, depth and width.

So I look at the length of the animal. I consider its width, through the loins and rib eye, and the width of stance and through the hindquarters. Lastly I look to see how deep is the muscle volume extending from the hindquarters down to the stifle. I like to see broader, rounder, longer steers.

My final consideration is to look at the overall fatness of the steer. It’s one thing to meet specifications. However it’s another to be evenly covered across the carcass. I look and feel over the major primals and over the carcass to see if the fat appears to be evenly distributed. Sometimes you can feel the fat coverage is uneven or hasn’t quite extended across the major areas.

As a carcass judge I’ve seen many bodies that are unevenly finished. This adds to the processors level of trim and overall reduces the value of the carcass to the processor. So its something I do try and consider and provide feedback on.

Essentially I use these three key areas to judge steers. Ultimately the steers that meet specification, display the high degree of muscle and even distribution of fatness are the ones I will select to be my place winners.

I don’t spend any time worrying about what the herd is like that produced these steers. I don’t worry about the heifers in the herd or anything outside of the ring. As a judge I can only assess what I see in front of me. Just as a buyer will only consider what is in front of them at the sale and if they will suit the processors needs. Focusing on these things does provide breeders with the information they need to fine-tune their program at home.

And for young people making their way into the industry, the lesson of knowing the market specifications, choosing cattle that suit their market and selecting for yield are lessons that will take them a long way into commercial and show ring success.

Know the risks of Nitrate & Prussic Acid in your feed

Feeding stock is a task that requires some prior preparation. While most feeds can be provided to ruminants, it doesn’t mean that you can feed them without following a few simple rules.

The rumen is a living environment, which hosts the micro-flora, fungi and other organisms that actually work to break feed down so that it can be absorbed and used by the animal. Sudden changes in feed type, lack or roughage and reduced water intake can all create a situation where the environment of the rumen becomes unhealthy to the micro-flora and results in digestive upsets and illness.

Mostly the rumen remains fairly stable as livestock select diets that allow the rumen micro-flora to thrive and do their job of breaking down material for absorption and digestion. Problems start to arise when diets and rations are offered that create unhealthy rumen environments.

As mentioned before common issues are changes in feed types, particularly to including grains that have high levels of starch. It also occurs when fibre is lacking or if rations are less than the animal requires and as it becomes hungrier it eats plants that may contain toxins that can result in illness or death.

Poisoning is a risk that many producers have had to consider this year. Common issues have been weeds that have been eaten as hungry stock eat whatever they can chew. It also has been an issue as new weeds arrive in drought feeds. Stock may consume plants that are poisonous simply because they have never seen them before.

However the biggest issue has been with sorghum crops that have been grazed or cut for fodder. The cause has been either from Nitrate poisoning or from Prussic Acid.

What is Nitrate Poisoning?

Nitrogen is needs by plants for growth. They absorb nitrogen through the soil and root system. Young plants and leaves have high levels of nitrates as they are growing. However when plants are stressed or not growing at a rate that allows the nitrogen to be used, the plant stores this as nitrate. Some plants are more prone than others to do this (they are known as ‘nitrate accumulators’), but most plants will accumulate nitrates to some degree if stressed.

The issue for livestock is that when the material is eaten that Nitrate is converted to nitrite. This chemical change allows the nitrite to be quickly absorbed from digested feed into the blood system where it attaches to hemoglobin. These nitrites replace oxygen cells in the blood and cause rapid impacts on the animal.

Within 15-20 minutes symptoms like staggering, difficulty breathing, spasms and foaming at the mouth start to occur. Many affected animals will lie down while some may thrash about. I’ve had it described to me that the cattle looked drunk.

Its mainly sheep and cattle impacted in this way. Horses and pigs are less affected by nitrate because they don’t convert it to nitrite. If levels are high though, the nitrate can damage the lining of their gut.

According to a number of sources, most of the species commonly grazed in Australia can cause nitrate poisoning if stressed. These are species that include oats, sorghum, maize, sudan grass, Johnson grass, canola, lucerne, kikuyu, turnip and sugar beet tops, soybean, wheat, barley and a range of weeds.

It’s essential that you consider feed testing any fodder that you purchase to see what level of nitrate is in the feed. Ask a few questions from the vendor? Was it treated with a big application of fertilizer or manure? Was it stressed before bailing? These questions can help you decide if it is suitable to feed to livestock

Prussic Acid

Prussic acid is a major concern for producers who graze or rely on sorghum varieties for fodder. It is present in most sorghum, although some varieties will have lower levels.

At a chemical level within the plant, prussic acids exist as a non-poisonous chemical called Dhurrin. This chemical can react with another plant-based material known as Emulsion. Under the right conditions, these two materials will react and create Prussic Acid. It’s also known as Hydrocyanic Acid. In simplest terms this is Cyanide Poisoning!

Damage to the pant through mechanical impact, environmental stress, trampling and even insect damage results in the mixing of these materials and the release of Cyanide.

While sometimes this can evaporate from the plant, it doesn’t all disappear. It also means that further damage, such as harvesting, or grazing will result in more Cyanide being released.

The concern with Prussic Acid is its high level of toxicity. Feed Central suggests that amounts greater than 0.1 percent (1000 ppm or mg/kg) of plant dry matter is considered highly dangerous. Some levels from the Washington State University place that level even lower at 750 ppm.

The effect on animals is very similar to that of nitrate poisoning. The acid is readily absorbed into the bloodstream and it then attaches to the hemoglobin and displaces oxygen.

Since many producers look to graze or use sorghum forage there are some basic considerations to be factored into the decision making process. Remember that:

Leaf blades normally contain higher levels than leaf sheaths or stems

Younger (upper) leaves have more prussic acid than older leaves

Tillers and branches (“suckers”) have the highest levels, because they are more leaf than stalk

Most sorghum should be grazed when they are more mature. Often this is over 3ft in height. As plants mature, there are more stalks than leaves in the overall plant causing prussic acid content in the plant as a whole to decrease.

With so much drought-affected crops its important to remember levels will be much higher as the pants are mostly leaves. Sorghum grown in drought may retain high levels of prussic acid, even if made into hay or silage.

My advice to all producers thinking about using or grazing sorghum is to get it tested first! Know the levels before you feed it out. There may be alternative uses to this feed.

If you do have concerns, or you want some more advice, then get in touch with me. Asking questions can save you a lot of risk and the potential of stock losses.

How long will your stock water last?

The summer of 2019 has been another very hot and dry season. Coming off one of the hottest years on record, with low rainfall, this summer has had a big impact on most agricultural programs.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for graziers will be access to reliable stock water. Of all the resources available to graziers, stock water is the most vital, and generally the most limiting. Water plays a role beyond ensuring survival. The quality of water offered will impact on feed intake levels and can restrict livestock production if it is outside acceptable ranges.

So how much do your animals consume? Daily consumption varies with the size of your animals, their production status. Obviously a lactating animal will require more water than a dry animal. The feed animals are consuming and weather conditions will also determine daily consumption levels.

As can be seen in this table, consumption for livestock is often higher than many people consider. Dry cattle for example will require between 50 – 70 litres a day depending on their size. However, hot conditions will see that level of consumption increase significantly.

Some research presented by Future Beef noted that rises of 10ºC (e.g. from 25ºC to 35ºC) can almost double daily consumption, particularly if there is high humidity as well. Its also important to recognize that lactating cows may have a 30% higher daily water intake than dry cows.

Water quality is a key factor in livestock intake. There are several components to water quality.

pH will impact on consumption and influence feed intake and rumen function. Low pH (more acid) will impact on rumen acidosis levels and suppress feed intake. While higher pH levels (more alkaline) will cause rumen upset, diarrhoea and poor feed conversion.

Salinity levels will also determine consumption levels. Salinity tests on water assess the sum of all mineral salts in water. Salinity can impact animal health as a result of their feed, temperature and humidity and the levels of salinity in the water itself

Algae, contaminants such as mud or debris from storm run off, and contamination from faeces are all issues that will restrict intake or cause health issues.

If you are concerned about the quality of the water your stock are accessing you can obtain water test kits from your State DPI or Agriculture Departments. (NSW DPI)(Western Australia)

How much water is in your dam?

Part of any plan regarding water is to know how much you have stored. Most people I speak with don’t really know how much they may have in a dam or in total, which can significantly add to the stress levels people feel.

The easiest way to work through estimating a dam’s water amount requires:

a tape measure

some very strong twine (like plumbers line)

two heavy duty lead sinkers

a dozen (or more) fishing floats.

Firstly you need to attach the sinkers to the end of the line. Then tie a slot every metre from the end of the line. Number each float with a large number suing a colour you can read easily.

Step 1: Measure two sides of your dam (this allows you to work out your surface area in square metres)

Step 2: Drag your sting across the deepest part of your dam and allow the floats to bring the line to vertical.

Step 3: Read the number of the float holding the line vertically.

Step 4: Multiply the surface area (From Step 1) by the depth you have just measured.

Step 5: To allow for the shape of your dam, multiply this figure by 0.4. This will tell you the total volume of your dam.

Step 6: To convert this total to mega-litres, divide the number by 1000.

Doing this exercise once a month will give you a fairly accurate stock take of water supply. If you calculate how many animals you have, and how much they drink each day, you will soon determine your overall levels of consumption.

Dividing this consumption by your total water supply will give you a time period for your current water supplies.

Effective plans need to have a time frame, and if your water supplies are the most limiting issue on farm, then it’s vital to have a time estimate. This estimate gives you the chance to make new plans and be proactive in your management, rather than responding or reacting when your options are much more limited.

When you do these evaluations, you will quickly determine that trucking water to stock is a task that can't be done effectively. The shear demand of water, let alone time and access may make the exercise extremely difficult. For many people trucking water is an impossibility when they realistically assess their livestock demand and the resources and time they have to meet the daily demand of livestock. Early planning will help you weigh up your options and focus you on using your limited resources as well as you possibly can.

If you need help in making plans or you require some advice, please don’t hesitate to get in touch. This is a key service I provide to producers and I’m happy to help where I can.

How Can You Help Our Rural Communities?

Across Australia, the impact of the extremes of climate is playing out with disastrous consequences for hundreds of families. Its been easy for some people in metropolitan NSW to think that the coastal rain and storms have been widespread. In fact the NSW DPI reveals in their latest Seasonal Update that the Combined Drought Indicator (CDI) has 99.8% of NSW experiencing drought conditions.

To break that down over a third of the state (36.8%) is classified as Intense Drought, The remaining areas of the state are considered wither in drought or drought affected. The impact of heat waves and above average temperatures, plus no rain has many producers on edge.

Of course the drought is not confined to NSW. Many parts of Queensland are now in the fifth or sixth year of drought. Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and parts of Western Australia have all recorded below average rainfall and are in drought or rapidly approaching drought conditions.

In Tasmania this has resulted in unprecedented bushfires. While many fires have impacted wilderness areas, there have been losses of homes, buildings and farming country.

Last week a huge part of North Queensland, some 20,000KM2 (almost the entire size of Kenya) was swamped by monsoon rain. This event has inundated stations, roads, railways and swept away 100’s of thousands of cattle. So many people in this region are struggling to start assessing the scale of their losses let alone even to consider rebuilding.

So what can you do to help? It’s a good question. The Australian way is to offer help and to want to look after those people doing it tough. I know that I feel that way myself.

The reality is, these events are huge. They will have an ongoing impact that will last for much longer than the news cycle or the next trend on Facebook. It extends across farms to impact businesses, towns and communities.

So any help that you would like to offer should be something that reflects the scale of the events and can be useful.

If you would like to offer or donate money, the Country Women’s Association have appeals that are directly focussed on communities. The CWA are community driven and have a long commitment of helping their community. In Qld, the QCWA Public Crisis Fund has been established to provide direct support in the event of disasters such as floods and fires. In NSW the CWA has established a fund specifically for drought aid. Alternatively the Australian Red Cross and St Vincent De Paul are charities that I have worked with and are focussed on direct assistance.

However, there are two other things you can do.

Go and visit these communities for a holiday.

When the worst of this is over, and communities start to rebuild, the money your visit brings in is essential. Small towns in the Huon Valley depend on tourism. In the Central West of NSW or the Far West, the difference your visit can make to a café, motel, and service station is just as important to a community as anything else you can do. And this is something you can do and make a difference in a real way over a longer term.

Support regional businesses.

It can be as easy as having an extra beef or lamb meal each week! However there are lots of small regional businesses that provide products and trade on line. Many of these support faming families with a little extra income. These little businesses are important to families, and communities so any support for them will have a direct benefit to people who need your help.

As communities recover over the coming months and years, don’t forget to check in on people you know. Keep visiting, keep supporting communities in these simple and practical ways. It will take a while to recover, so these are ways you can help for a longer time than just in the immediate aftermath of the disasters we are seeing right now.

Think safe in the heat!

This week I was talking with a colleague from the south west of the state. The topic of conversation was the recent heat waves and how they have been coping with it. One of the points they mentioned was the decision to postpone a sheep sale to avoid the worst of the heat, and then to start subsequent ones earlier in the day.

I thought that was a great move. Apparently while there was general support, there were still some people who were critical of the move! I’ve been scratching my head about that for a few days now!

All I can put that criticism down to is that there are just some people who like to criticise. However, it does expose the school of thought that does seem to prevail with some people that unless you are uncomfortable, you aren’t working hard enough!

I really struggle with that idea. I don’t think its helpful and often leads people to make decisions that can actually be dangerous. I think we tend to underestimate the impact that heat has on us. I know that I have often failed to consider the impact that heat and manual work will have on me. It's important to remember that there is a big difference between being hot, and overheating. Overheating can have some pretty serious impacts that if not addressed can lead to death.

Heat Exhaustion is something many people have experienced. It's often characterized by sings like headaches; increased thirst; dizziness and nausea. However if it's ignored it could continue to show itself with poor coordination, anxiety and poor decision making.

Heat exhaustion can be pretty debilitating and requires some immediate attention. Ideally you should lie down in some air conditioning or shade; drink plenty of water. If you are very hot, then cooling your body with a cold shower or bath can also help.

As a firefighter, we often had to cool down on protracted incidents. Not having access to showers or baths, we would take off as much clothing as we could (down to shirts and pants) and then we would often rest our forearms in buckets of water or in chairs that had arm rests which we filled with water before putting our hands and arms in the water.

As a firefighter, we often had to cool down on protracted incidents. Not having access to showers or baths, we would take off as much clothing as we could (down to shirts and pants) and then we would often rest our forearms in buckets of water or in chairs that had arm rests which we filled with water before putting our hands and arms in the water.

There is some neat research that shows immersing your arms and hands in water and sitting in the shade cools your core temperate down much more quickly than simply resting in the shade.

If you don’t address the signs of heat exhaustion, you risk the more drastic impact of heat stroke. Heatstroke occurs when a persons temperature is greater than 40°C. As a result they may then experience confusion, convulsions, or coma.

As with the symptoms of heat exhaustion, heatstroke could see a person have:

headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting and confusion

having flushed, hot and unusually dry skin

being extremely thirsty

having a dry, swollen tongue

having a sudden rise in body temperature to more than 40°C

being disoriented or delirious

slurred speech

being aggressive or behaving strangely

convulsions, seizures or coma.

may be sweating and skin may feel deceptively cool

rapid pulse

Heat stroke is not to be taken lightly! If you notice any of the above signs of heatstroke in yourself or others, call 000 immediately for an ambulance. If you don’t treat heat stroke it can lead to permanent damage to vital organs or even death.

Heat can effect people very quickly. Its vital not to think that you can’t be impacted or that you can get used to it! While we think about the impact of heat, the time it takes to get over a case of exhaustion can see you recovering for a few days.

Given the risks that heat poses, I reckon any plan to postpone work until its cooler is a sensible option. There’s nothing so important it cant wait for a bit!

Using Scrub as a Livestock Feed

The search for roughage during a drought challenges many producers. Over many years, scrub and some native trees have become a ‘go to’ for producers seeking an alternative and cheap source of feed.

Many people have used scrub very successfully as part of their drought programs. However there are equally many occasions where results have been disappointing or have actually increased problems within the livestock program.

Image: ABC New England

So, just how good is scrub? I know many people will swear to the value of species such as Kurrajongs, Wilga or Native Apple. Mulga is an important species in the inland parts of the country.

However as with any feeding program, it’s never really that simple!

As can be seen in the table above, there is a fair bit of variation in the nutritional ranges of commonly fed species. Most species have an energy range of 7.5 MJ / Kg to 10.5MJ /kg. However in general the average is around 8.5MJ. In general its fair to say that the best-case scenario for scrub is that it is the equivalent of average quality hay. At these levels you really only expect scrub to provide maintenance levels of energy, provided your animals can eat enough each day!

The limitation for many scrub feeds is the level of Crude Protein (CP%). Many of the feeds that have been tested only provide enough CP to meet the maintenance requirements for dry animals. In practice this really means that if you are feeding to animals that are growing, pregnant or lactating, you will have to use a suitable protein supplement to meet these animals daily needs.

Not all stock will take to scrub. And not all scrub is as palatable as you might expect. It is important to use some local knowledge when looking at including scrub in your rations.

If you do start to use scrub, there are a few things to remember. Its important to try to use scrub that has a fair bit of leaf. Increasing twigs and small branches reduces animals overall intake of energy and protein. It also leads to risks of rumen impaction.

When working with producers who have had scrub in their programs, I’ve seen some useful tips. To educate your stock to scrub, start with small amounts close to watering points and stock camps. If needed you can spray a water molasses mix (2 parts molasses to 1 part water) onto the scrub.

When the stock recognize the sound of the saw, you should move away from these area and use trees and stands furthest from water. That way you can preserve the trees closer to water sources for when its hotter or if animals are weaker and won’t browse as far.

Impaction can be a real issue, particularly if there is not enough leaf material in the diet. Twigs can be an issue. Feeding molasses in troughs can help reduce this risk. Its also worth providing a supplement of ground limestone in the molasses mix at 1.5%. This will help maintain animals intakes of calcium.

Signs such as depressed appetite, no cud chewing or discomfort, often characterize impaction. You might notice animals groaning or even kicking their bellies.

Providing a protein supplement can also reduce the risk of impaction. A supplement will help stimulate rumen function and ensure material is digested more effectively. Suitable choices could be molasses and cottonseed meal (fortified molasses mix) or white cottonseed.

If you are cutting scrub, remember if you don’t cut enough, animals will be forced to eat more twigs and small branches. This can also increase the risk of impaction.

The final important consideration when feeding scrub is access to sufficient water. Stock must be able to access enough water each day. Reduced water intake can rapidly increase the risk of impaction, so water sources need to be clean as well as reliable.

Finally a couple of tips. Try to use only one species at a time. Otherwise stock might waste feed by choosing one species over the other. In hot weather you might have to feed more frequently than a typical 2-3 day program. Daily cutting might help avoid leaf loss as scrub dries out in the heat and becomes inaccessible to stock.

It is important to consider the way you cut and lop scrub. For regrowth its essential that you try not to cut too heavily, particularly preserving the trunk and major braches. Some foliage should be left to help the tree recover, ideally above stock browsing height. You should also really only lop a tree once a season to allow it to recover, although depending on the length of the drought, this period may be much longer.

Your own safety is vital! Climbing trees and using chainsaws are dangerous undertakings. When you are hot, tired or stressed the risk of injury is much greater. So consider ways to be safe. Can you do it early when its cool and you are not tired? Can you access a cheery picker or other method that means you don’t need to climb trees.

Keep thinking is there a SAFER way!

Finally after a few months, stock will lose their appetite for scrub. So I reckon it is important that your plan takes this into account. If you don’t know what the next phases might be, then why don’t you get in touch with me and we can work a plan out together.

Understanding your feed test results

How good is the feed you are offering to your livestock?I think this is a tricky question to ask.I know that in 90% of the instances that I’ve asked a farmer this question, their response is generally “Oh its pretty good!”Sometimes the qualification is offered that someone they knew grew it, or that it cost a lot to buy!

Unfortunately cost isn’t actually an indicator of the feed value!

Feed value is actually determined by levels of energy; crude protein; digestibility, fibre and the amount of moisture contained in the feed. All these components contribute to the usefulness a particular feed has in meeting animals nutritional needs as well as impacting on the amount the animal can physically consume each day.

It’s actually pretty difficult to tell any of these things from a visual inspection. And while looking at a hay, or silage you might be able to have a guess it the digestibility of the plant when it was cut and the general moisture content, its only ever going to be a guess.

Over the past few months, many people have been full feeding their animals as the drought restricts paddock feed. A lot of these rations have been well planned and meet the various needs of the stock. However there are still plenty of rations put together on the basis of guess work! And by guessing some classes of stock are being underfed.

Obtaining a feed test is the most reliable way to determine the value of a feed. Its also is essential if you want to develop a ration that actually meets the needs of your stock.

Feed tests kits can be obtained through private companies or state departments of agriculture. Pretty much any feed can be tested. The kits will provide instructions regarding the amount you nee to collect to send away.

There are various levels of testing that you can request. For most situations, a standard evaluation is enough to give you the information that will help you know how useful your feed really is.

The things I look for include the following key components:

DRY MATTER (DM): All feeds contain some amount of moisture. This moisture has no nutritional value. When you prepare a ration, you need to allow for the water in the feed, and in many cases you will actually have to increase the physical or ‘as fed’ amount per animal to account for the moisture. If you don’t, your rations may end up being lower than what your stock need each day. Over a period of time, this can lead to significant underfeeding!

DRY MATTER DIGESTIBILITY: This explains as a percentage, how much of a feed your animals will be able to digest. Digestibility and energy are positively related, so having high levels of digestibility not only means your animals can use more of a feed, it also means that the energy levels of the feed are at a level that will meet their needs.

DRY ORGANIC MATTER DIGESTIBILITY: A further measure of digestibility is made on the organic matter of the feed. It is expressed as a percentage and again the higher the percentage, the higher value of the feed for animal production.

CRUDE PROTEIN: Crude Protein is expressed as a % of the Dry Matter. Crude Protein is essential for rumen function. Low levels will reduce the ability of a rumen population to effectively use a feed. For maintenance cattle require Crude Protein to be a minimum of 8%. Lower values may mean that you will need to add a protein source to your ration.

FIBRE: Fibre is an important part of a diet. Low levels of fibre can lead to digestive upsets. More commonly, in rations I’ve seen recently, fibre is often very high. High fibre not only lowers digestibility (and energy) but it will also reduce the amount of feed an animal will actually eat.

Fibre is measured by either; Acid Detergent Fibre (ADF) or Neutral Detergent Fibre (NDF). Acid Detergent Fibre (ADF) is a measurement of cellulose and lignin while